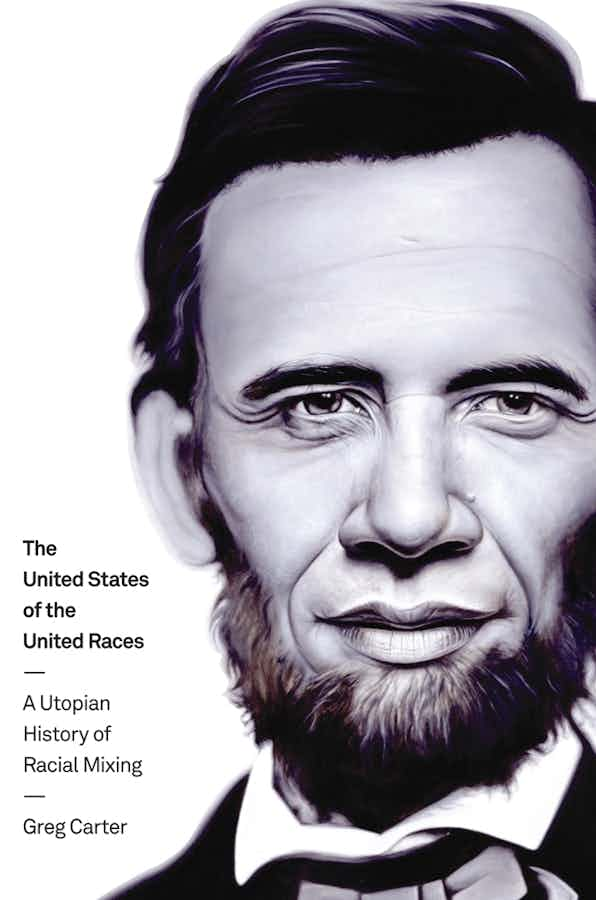

The United States of the United Races: A Utopian History of Racial Mixing

New York University Press

April 2013

288 pages

22 halftones

Cloth ISBN: 9780814772492

Paper ISBN: 9780814772508

Greg Carter, Associate Professor of History

University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

Barack Obama’s historic presidency has re-inserted mixed race into the national conversation. While the troubled and pejorative history of racial amalgamation throughout U.S. history is a familiar story, The United States of the United Races reconsiders an understudied optimist tradition, one which has praised mixture as a means to create a new people, bring equality to all, and fulfill an American destiny. In this genealogy, Greg Carter re-envisions racial mixture as a vehicle for pride and a way for citizens to examine mixed America as a better America.

Tracing the centuries-long conversation that began with Hector St. John de Crevecoeur’s Letters of an American Farmer in the 1780s through to the Mulitracial Movement of the 1990s and the debates surrounding racial categories on the U.S. Census in the twenty-first century, Greg Carter explores a broad range of documents and moments, unearthing a new narrative that locates hope in racial mixture. Carter traces the reception of the concept as it has evolved over the years, from and decade to decade and century to century, wherein even minor changes in individual attitudes have paved the way for major changes in public response. The United States of the United Races sweeps away an ugly element of U.S. history, replacing it with a new understanding of race in America.

Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Thomas Jefferson’s Challengers

- 2. Wendell Phillips, Unapologetic Abolitionist, Unreformed Amalgamationist

- 3. Plessy v. Racism

- 4. The Color Line, the Melting Pot, and the Stomach

- 5. Say It Loud, I’m One Drop and I’m Proud

- 6. The End of Race as We Know It

- 7. Praising Ambiguity, Preferring Certainty

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author

Introduction

In April 2010, the White House publicized Barack Obama’s self-identification on his U.S. census form. He marked one box “Black, African Am., or Negro,” settling one of the most prevalent issues during his 2008 presidential campaign: his racial identity. This choice resounded with the monoracial ways of thinking so prevalent throughout U.S. history. People who believed he was only black because he looked like a black person or because many others (society) believed so or because of the historical prevalence of the one-drop rule received confirmation of that belief. The mainstream media had been calling him the black president for over a year, so they received confirmation of this moniker.

Many people who had followed the adoption of multiple checking on the census found his choice surprising. Surely, as president, he would be aware of the ability to choose more than one race. To pick one alone went against everything activists wanting to reform the government’s system of racial categorization had worked for in the 1990s. Many found it surprising that the man who had called himself “the son of a black man from Kenya and a white woman from Kansas” would choose one race. After all, he had used this construction far more times than he had called himself black, giving the impression that he embraced his mixture along with identifying as black. That snippet, along with images of his diverse family, had been part of what endeared him to mixed-race supporters. Similarly, his campaign’s deployment of his white relatives built sympathy with white voters. Some people argued that he had failed to indicate what he “was” by choosing one race. He made the diverse backgrounds in his immediate family a footnote. But, recalling Maria P. P. Root’s “A Bill of Rights for Racially Mixed People,” a pillar of contemporary thought on mixed race, they had to respect his prerogative. He had the right to identify himself differently than the way strangers expected him to identify.

Three lessons emerged from this episode: How one talks about oneself can be different from how one identifies from day to day. How one identifies from day to day can be different from how one fills out forms. And on a form with political repercussions, such as the census, one may choose a political statement different from both how one talks and how one identifies. Obama had always been a political creature; he never did anything for simple reasons. By the regulations, the administration could have withheld the information for seventy-two years. Instead, it became a small yet notable news piece in real time. Publicizing his participation in the census could motivate other minorities (beyond those who knew the history of multiple checking) to do so as well. More likely, he was thinking about the 2012 election. His response to the 2010 census could influence voters later on. If the number of those who would have hurt feelings over a singular answer was less than those who would find offense in a multiple answer, then a singular answer was the best to give. Even though mixed-race Americans took great pride in Obama’s ascendance, they were a small faction to satisfy.

Then why did Obama take so much care to cast himself as a young, mixed-race hope for the future? Because even though the number of people who identify as mixed race is small, they hold immense figural power for the nation as symbols of progress, equality, and utopia, themes he wanted to associate with his campaign. In other words, he piggybacked onto positive notions about racially mixed people to improve his symbolic power. At the same time, he nurtured the stable, concrete, and accessible identity that people so used to monoracial thought could embrace, not the ambiguous one that challenged everyone.

Interpretation of current events such as this can disentangle the complexities we encounter here and now. However, while historical analysis always enriches the understanding of current events, writing history about current events presents a pitfall: they are moving targets resisting our attempts to focus on them. Similarly, following figures such as Obama lures us into announcing sea changes in racial conditions. Americans of all walks like indicators of progress. But addressing racial inequality calls for more than well-wishing. As a guiding principle, we should remember to appreciate that these are stories that have no resolution, much like the story of racialization in general. The meanings of mixture, the language we use to describe it, and its cast of characters have always been in flux.

Even before colonial Virginia established the first anti-intermarriage laws in 1691, efforts to stabilize racial identity had been instrumental in securing property, defending slavery, and maintaining segregation. The study of interracial intimacy has labeled racially mixed people either pollutants to society or the last hope for their inferior parent groups. To this day, many Americans label each other monoracially, interracial marriage remains a rarity, and group identities work best when easy to comprehend. However, at the same time that many worked to make racial categorization rigid, a few have defended racial mixing as a boon for the nation. Ever since English explorer John Smith told the story of the Indian princess Pocahontas saving his life in 1608 (a founding myth of the United States), some have considered racial mixing a positive. These voices were often privileged with access to outlets. Many were men, and many were white. This study reconsiders the understudied optimist tradition that has disavowed mixing as a means to uplift a particular racial group or a means to do away with race altogether. Instead, this group of vanguards has praised mixture as a means to create a new people, to bring equality to all, and to fulfill an American destiny. Historians of race have passed over this position, but my narrative shows that contemporary fascination with racially mixed figures has historical roots in how past Americans have imagined what radical abolitionist Wendell Phillips first called “The United States of the United Races.”…

Read the entire Introduction here.