Emma Dabiri: ‘When race begins and ends with social media, we have quite reductive, distorted interpretations of what we’re dealing with’Posted in Articles, Biography, Europe, Media Archive, Social Justice, United Kingdom on 2021-09-27 18:52Z by Steven |

The Irish Independent

2021-07-18

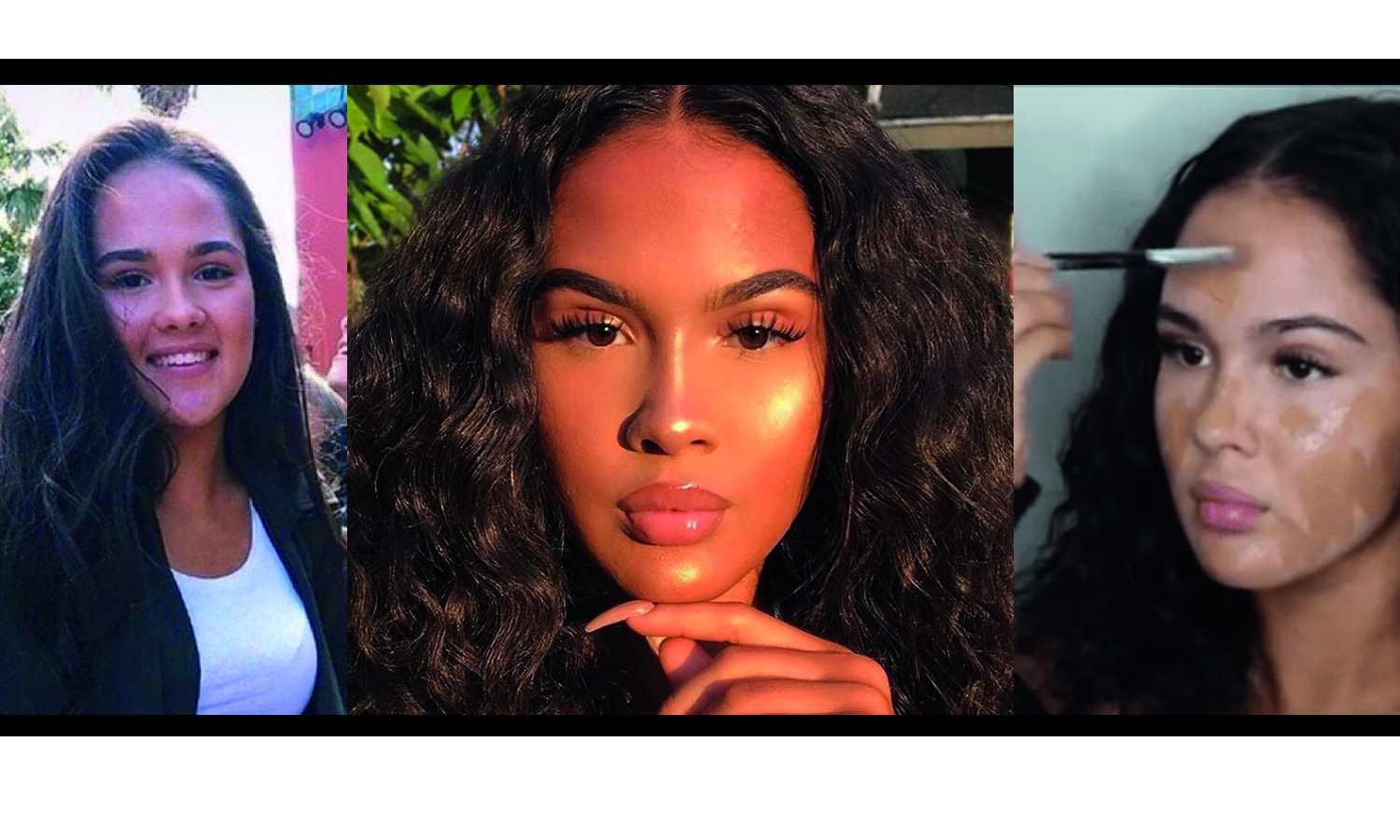

Writer Emma Dabiri, photographed by Steve Ryan

Irish-Nigerian writer and academic Emma Dabiri talks about growing up in Ireland as an outsider, how this shaped her activism and career, and why leisure is liberation

‘I had already been angry, had spent most of my life angry,” Emma Dabiri writes in her latest book, What White People Can Do Next. She’s talking about her reaction to the murder of George Floyd in America last May at the hands of a police officer, and the subsequent protests that broke out around the world.

Now, though, she no longer gets angry. Last summer’s events were, Emma reflects, in terms of racism, “just business as usual”.

She recalls wryly now how people contacted her in the wake of Floyd’s murder.

“So, for me, it’s completely horrific, but why was it that murder that sparked the world? State-sanctioned killing has been happening regularly for centuries; that one captured the public’s imagination,” she says.

“I had people messaging me saying ‘this time must be unbearably distressing for you’, and I’m like, well, why is it wildly more distressing than any of the millions of other times this has happened? Because you happened to hear of it this time? Because this time it happened to move you? Why do you think this is the first time I’m engaging with something like this?”

Broadcaster, author and academic Emma, whose father was Nigerian and whose mother is Irish, was born in Dublin but moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where she lived before returning to Ireland with her mum when she was four. She grew up here in the 1980s and early 1990s, before moving to London when she was 19.

“I experienced racism from quite a young age. My response to those experiences was to read, and try and make sense of what I was experiencing through reading,” explains Emma, who left Ireland to do a degree in African studies and post-colonial theory at SOAS University of London.

She understood racism at an early age: “These weren’t things that I decided, or discovered recently, I have been living and working with and through this stuff for many, many years.”…

Read the entire article here.